January 23rd, 2011 § § permalink

Has it really been over three months since my last post? Between becoming one of the next Co-Editors in Chief of Fertility and Sterility, preparing for a review of our urology training program and finishing my latest book (Thank You, Chapter Authors!) I guess that I’ve let my blogging slip a bit. Fortunately, thanks to my Italian co-faculty’s discovery of the Saeco Vienna Plus espresso maker at Costco, I’m back at the keyboard.

I turned off the two-week limit for comments, and so far, that’s been a good idea. People are commenting on older posts (like How Clomid Works in Men) with good questions and thoughtful points. For new commenters, please read the FAQ. I can’t answer questions about specific patients. Those are best left to a live visit with a doctor with an interest in male reproductive medicine. One great resource is the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s Society for Male Reproduction and Urology page and the ASRM’s find a doctor search page, (just click on the “Society for Male Reproduction and Urology (SMRU)” button in the “Find Member by Affiliated Society:” section.) Another excellent way to find a specialist who treats men with reproductive issues is to use the American Urological Association’s Society for the Study of Male Reproduction’s search engine.

This blog post was inspired by several patients who asked after I explained surgical sperm retrieval, if there was somewhere they could go for more information. I realized that I hadn’t written about such a common issue.

Just as a carpenter has many ways to make a cabinet, a surgeon can tackle a problem in a number of ways. And just as two cabinets may differ, different surgical problems demand different approaches. Such is the case in retrieving sperm from the testis.

Most of the time, taking sperm directly from the testis is necessary when a man has azoospermia, where no sperm is found in the ejaculate. Azoospermia takes two basic forms, obstructive and non-obstructive. As the name implies, obstructive azoospermia is due to a blockage in the tubes and structures that convey sperm from the testis to the outside world. In the best case, a surgeon can fix the errant anatomy, allowing a couple to conceive children without further ado. But because the tubes are so tiny, sometimes the tubes can’t be reconnected with surgery, and the alternative is to take sperm from the testis for it to be used in in-vitro fertilization.

The other form of azoospermia, non-obstructive, arises when the factory making sperm in the testis isn’t working quite right. Sometimes, the cells starting sperm are missing entirely, a condition known as “Sertoli cell only syndrome”. Occasionally, sperm may be rolling along their assembly line, a process that takes two to three months to complete, and stop mid-production. When that happens, it’s called “maturation arrest“. But frequently, sperm can be found in small amounts in the testis and can be retrieved using surgery.

Because it isn’t mature, sperm from the testis can only be used with in-vitro fertilization and intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection.

Because it isn’t mature, sperm from the testis can only be used with in-vitro fertilization and intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection.

How can a surgeon remove sperm? He or she can take it from the testis itself, or the epididymis, the tiny coiled tube lying on the back of the testis where sperm mature. The surgeon can insert a needle into the testis or epididymis, he or she may make one or several small incisions into the testis or use microsurgery to retrieve sperm from either the testis or epididymis. In the case of obstructive azoospermia, it doesn’t seem to matter which technique is used. There’s plenty of sperm wherever it’s sought, and any method will do to retrieve it. When a man has obstructive azoospermia, I usually recommend taking a small piece from the testis, as the sperm may be frozen and is good for a number of in-vitro fertilization cycles so that the man doesn’t need to go through a procedure for every cycle, and can be there for his wife during her procedures.

We’ve found that frozen sperm is just as good as fresh. in fact, the chances for fertilization are the same for fresh and frozen sperm, and the chance for pregnancy may even be a little better for frozen sperm than for fresh.

We’ve found that frozen sperm is just as good as fresh. in fact, the chances for fertilization are the same for fresh and frozen sperm, and the chance for pregnancy may even be a little better for frozen sperm than for fresh.

Frozen sperm should literally last forever. It’s in liquid nitrogen, which is so cold that the building blocks making sperm don’t decay. Freezing sperm gives a couple time to plan when in-vitro fertilization is done.

Frozen sperm should literally last forever. It’s in liquid nitrogen, which is so cold that the building blocks making sperm don’t decay. Freezing sperm gives a couple time to plan when in-vitro fertilization is done.

When he has non-obstructive azoospermia, a man’s options are more limited. A surgeon can use the operating microscope to comb through the testis looking for areas that may contain sperm, a procedure known as “microsurgical testis sperm extraction“. Other techniques include making several small incisions in the testis or piercing the testis with a needle in a dozen or so different spots. When a man has non-obstructive azoospermia, I usually recommend microsurgical testis sperm extraction. More areas of the testis can be examined, and I can see the places that most likely contain sperm.

We’ve observed that prescribing a man with non-obstructive azoospermia clomiphene citrate for a few months before surgical retrieval seems to increase the chance to retrieve sperm. In many men, sperm appears in the ejaculate and surgery isn’t needed. If a couple has a few months, taking clomiphene before surgical sperm retrieval might be a good idea.

In short, a surgeon has many ways to retrieve sperm when necessary. The choice depends on the preference of the surgeon and the couple, and what’s going on inside the testis. I’ve listed the surgical techniques available, and my typical recommendations.

July 6th, 2010 § § permalink

|

Doctor’s Corner

|

Ever so often, I get asked questions from doctors, and I figure that here is a reasonable place to put how I answer the frequently asked ones. As with everything I write, it’s my opinion, and doctors opinions vary.

One question I get asked a lot is how to prescribe clomiphene for a male. Here’s how I do it.

First, clomiphene works by stimulating the pituitary. If the pituitary’s already in overdrive, clomiphene won’t help. So if a man’s LH is high, like 25 IU/L, I don’t prescribe clomiphene.

The next decision to make is what the target for therapy will be. If it’s augmenting a low testosterone level, then I’ll use the bioavailable testosterone calculation described in a previous post. As a reasonable threshold for total testosterone is 300 ng/dL and the portion of bioavailable testosterone ranges between 52% and 70%,1 I use the range between 156 ng/dL to 210 ng/dL as a lower limit of what is likely an adequate bioavailable testosterone level for a man. If the target for clomiphene therapy is stimulating the testis to make sperm, I use a higher threshold. If possible we try for twice as much, about 400 ng/dL for bioavailable and 600 ng/dl for total testosterone. It’s not always possible to achieve those levels.

I start with 25 mg clomiphene a day. As the pills come in 50 mg, and the half-life is relatively long, patients can take a pill every other day. Some prefer talking half a 50 mg pill daily. After two weeks, I have the patient get tests for testosterone, LH, albumin, SHBG (sex hormone binding globulin) and estradiol. In some instances, the estradiol will increase, but as long as the ratio of total testosterone to estradiol is greater than ten-to-one, that shouldn’t be a problem. If the estradiol increases substantially, other therapy, like an aromatase inhibitor, is preferred. If the testosterone is still low, then we’ll increase the clomiphene by 25 mg every other day or daily, and repeat the tests. I’ll increase the clomiphene to a maximum of 100 mg daily.

I believe that clomiphene works better if a man’s testosterone is low. That’s a good indication that there is a problem that may be corrected. If the testosterone is reasonable at the start, 400 ng/dL or more, then pushing it higher may not be as effective. But that’s my opinion, and as of present, scientific studies don’t definitively prove it right or wrong.

It’s important to note that clomiphene is “off-label” for use in the male. I explain this in a previous post.

1S. Bhasin. Chapter 18: Testicular disorders. In: Kronenberg H. M., Melmed S., Polonsky K. S., and Reed Larsen P., eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology 11th ed. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders Company, 2008; 647.

April 28th, 2010 § § permalink

With the suspension of Cincinnati Reds pitcher Edinson Volquez for performance enhancing drug use and a swirl of rumors that the agent involved was clomiphene (also known as Clomid,) I thought it timely to write about how clomiphene works and how it’s used. From what I read on the internets, there is an enormous amount of misinformation floating around out there.

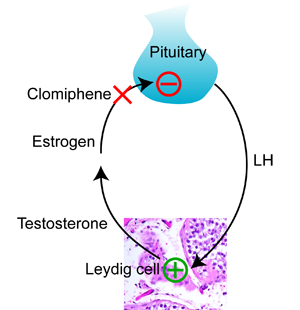

To understand how clomiphene works, you need to know how the pituitary controls the making of testosterone in the testis. Testosterone is made by Leydig cells in the testis, which I explained in my last post. The pituitary releases a hormone called luteinizing hormone (“LH”) that stimulates the Leydig cells to make testosterone. Testosterone is converted to the female hormone estrogen, (which I also explained in my last post,) and estrogen tells the pituitary to stop making more LH. This kind of negative feedback system is common when it comes to how hormones work. It’s just like a thermostat and heater. As the room gets warmer, the thermostat sends less electricity to the heater. When the room gets colder, the thermostat sends more electricity to the heater.

Clomiphene works by blocking estrogen at the pituitary. The pituitary sees less estrogen, and makes more LH. More LH means that the Leydig cells in the testis make more testosterone.

As I explained in my last post, giving testosterone to a man does just the opposite. The pituitary thinks that the testis is making plenty of testosterone, and LH falls. As a result, the testis stops making testosterone, and the usually high levels of testosterone in the testis fall to the lower level in the blood.

So clomiphene is a way to increase testosterone in the blood and the testis at the same time. It preserves testis size and function while increasing blood testosterone.

Unfortunately, clomiphene is not FDA approved for use in the male. Like most of the medications that we use to treat male fertility, the pharmaceutical company that originally sought approval by the FDA did it for women. Clomiphene is now generic, and it’s unlikely that anyone will pony up the hundreds of millions of dollars necessary to get it approved for the male. That’s the bad news. The good news is that it means that this medication is fairly inexpensive, cheaper than most forms of prescription testosterone. Can a doctor prescribe clomiphene for a man? Yes. It’s “off label”, meaning that it’s not FDA approved for use in men.

As a medication, clomiphene is usually well tolerated by men. In my experience, most patients don’t feel anything as their testosterone rises. Those that do feel an increase in energy, sex drive, and muscle mass, especially if they work out. Very rarely I’ve had patients report that they feel too aggressive, or too angry. Very very rarely (twice in the last 20 years) I’ve had patients report visual changes. That’s worrisome, as the pituitary is near the optic nerve in the brain, and visual changes suggests that the pituitary may be changing in size. Because the skull is a closed space, it’s alarming if anything in the brain changes in size. In the last twenty years, I’ve also had two patients who had breast enlargement (called “gynecomastia”) while using clomiphene. Needless to say, for any of these problematic side effects, the clomiphene is discontinued.

So that’s the story with clomiphene. It can be used in the male, either for fertility or low testosterone levels. It’s an off label prescription drug. It works, and is usually well tolerated by men who take it.

![]() Because it isn’t mature, sperm from the testis can only be used with in-vitro fertilization and intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection.

Because it isn’t mature, sperm from the testis can only be used with in-vitro fertilization and intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection.![]() We’ve found that frozen sperm is just as good as fresh. in fact, the chances for fertilization are the same for fresh and frozen sperm, and the chance for pregnancy may even be a little better for frozen sperm than for fresh.

We’ve found that frozen sperm is just as good as fresh. in fact, the chances for fertilization are the same for fresh and frozen sperm, and the chance for pregnancy may even be a little better for frozen sperm than for fresh.![]() Frozen sperm should literally last forever. It’s in liquid nitrogen, which is so cold that the building blocks making sperm don’t decay. Freezing sperm gives a couple time to plan when in-vitro fertilization is done.

Frozen sperm should literally last forever. It’s in liquid nitrogen, which is so cold that the building blocks making sperm don’t decay. Freezing sperm gives a couple time to plan when in-vitro fertilization is done.